Did Epiphany really happen?

The Banquet of the Epiphany in the church's liturgical calendar is based on the events of Matt ii.1–12, the visit of the 'wise men' from the E to the infant Jesus. At that place are plenty of things almost the story which might make us instinctively treat it equally just another function of the constellation of Christmas traditions, which does not have very much connection with reality.

The Banquet of the Epiphany in the church's liturgical calendar is based on the events of Matt ii.1–12, the visit of the 'wise men' from the E to the infant Jesus. At that place are plenty of things almost the story which might make us instinctively treat it equally just another function of the constellation of Christmas traditions, which does not have very much connection with reality.

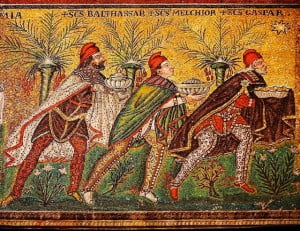

The first is the sparseness of the story. As with other parts of the gospels, the details are given to united states in bare outline compared with what we are used to in modern literature. Nosotros are told niggling of the historical reality that might interest us, and the temptation is to fill in details for ourselves. This leads to the second issue—the development of sometimes quite elaborate traditions which do the work of filling in for us. And then these 'magoi' (which gives us our discussion 'magic') became '3' (because of the number of their gifts), and so 'wise men' and then 'kings' (probably under the influence of Ps 72.10. Past the time of this Roman mosaic from the church in Ravenna built in 547, they take even caused names. Christopher Howse comments:

Yet, that is non entirely what the Gospel says…

In response to this, critical scholarship has moved in the other direction, and by and large has pulled apart Matthew's story and confidently decided information technology that none of it really happened. Instead, information technology was constructed by Matthew out of a series of OT texts in social club to tell us the real significance of Jesus. So Marcus Borg and Dominic Crossan, inThe First Christmas: what the gospels really teach about Jesus' nativity, come to this conclusion:

In our judgement, at that place was no special star, no wise men and no plot by Herod to kill Jesus. And then is the story factually true? No. But as a parable, is it true? For us equally Christians, the answer is a robust affirmative. Is Jesus light shining in the darkness? Yes. Do the Herods of this world seek to extinguish the light? Yes, Does Jesus all the same polish in the darkness? Yes. (p 184).

The arroyo presents problems of its own. For one, the stories are not presented as parables, but in continuity with the events Matthew relates in Jesus' life later in the gospel. For another, if God in Jesus did non outwit Herod, on what grounds might we think he can outwit 'the Herods of this world'? More fundamentally, Matthew and his start readers appeared to believe that the claims about Jesus were 'parabolically true' because these things actually happened. If none of them did, what grounds do we now have? Even if the events we read about are heavily interpreted, at that place is an irreducible facticity in testimony; if this has gone, we ought to question the value of the testimony itself.

A skilful working instance of this approach is found in Paul Davidson'southward blog. Davidson is a professional translator, rather than a biblical studies bookish, only he offers a good outline of what critical scholarship has to say almost Matthew'south nativity.

His bones assumption is that Matthew is a 'multi-layered' document—Matthew is writing from the basis of other, differing sources. He takes over large parts of Marking'due south gospel, as does Luke, and Matthew and Luke never hold in contradiction to Marker, a cardinal piece of the argument of 'Marcan priority', that Marker was earlier than either of the other two. Whether or not you believe in the existence of the so-called Q, another early written source (and with Mark Goodacre, I don't), Matthew is clearly dealing with some pre-existing material, oral or written. Information technology is striking, for example, that Joseph is a central character in Matthew's account before and after the story of the magi, and is the primal histrion in contrast to Luke's nativity, where the women are cardinal. Still in this section (Matt 2.1–12) the focus is on 'the kid' or 'the child and his mother Mary' (Matt two.ix, ii.11; see also Matt two.14, 20 and 21). Some scholars therefore argue that this story comes from a dissimilar source, and so might be unhistorical.

This is where nosotros need to start being disquisitional of criticism. Handling texts in this way requires the making of some bold assumptions, not to the lowest degree that of author invariants. If a modify of style indicates a change of source, and then this can only exist seen if the writer is absolutely consistent in his (or her) own writing, and fails to brand the source cloth his or her ain. In other words, we (at 20 centuries distant) demand to be a lot smarter than the author him- or herself. Even a basic appreciation of writing suggests that authors are just not that consistent.

Davidson goes on in his exploration to explicate the story of the star in terms of OT source texts.

The basis for the star and the magi comes from Numbers 22–24, a story in which Balaam, a soothsayer from the east (and a magus in Jewish tradition) foretells the coming of a great ruler "out of Jacob". Significantly, the Greek version of this passage has messianic overtones, every bit information technology replaces "sceptre" in 24:17 with "man."

He is quite right to identify the connections here; any good commentary will indicate out these allusions, and it would exist surprising if Matthew, writing what most would regard as a 'Jewish' gospel, was not aware of this. But if he is using these texts as a 'source', he is not doing a very good job. The star points to Jesus, but Jesus is non described as a 'star', and no gospels make utilise of this as a title. In fact, this is the only identify where the discussion 'star' occurs in the gospel. (Information technology does occur equally a title in Rev 22.16, and mayhap in ii Peter i.19, but neither make any connexion with this passage.)

Adjacent, Davidson looks at the commendation in Matt 2.v–half dozen, which for many critical scholars provides the rationale for a passage explaining that Jesus was born in Bethlehem when he is otherwise universally known every bit 'Jesus of Nazareth' (19 times in all four gospels and Acts). Just, as Davidson points out, Matthew has to work difficult to get these texts to help him. For one, he has to bolt together ii texts which are otherwise completely unconnected, from Micah v.2 and 2 Sam 5.ii. Secondly, he has to alter the text of Micah 5.2 and then that:

- Bethlehem, the 'least' of the cities of Judah, now becomes 'by no means the to the lowest degree';

- the well-known epithet 'Ephrathah' becomes 'Judah' to make the geography clear; and

- the 'clans' becomes 'clan leader' i.e. 'ruler' to brand the text relevant.

Moreover, Matthew is making utilize of a text which was not known as 'messianic'; in the outset century, the idea that messiah had to come from Bethlehem as a son of David was known only not very widespread.

All this is rather bad news for those who would argue that Jesus' birth was advisedly planned to be a literal fulfilment of OT prophecy. Simply it is equally bad news for those who argue that Matthew made the story upwards to fit such texts, and for exactly the same reason. Of course, Matthew is working in a context where midrashic reading of texts ways that they are a good bargain more flexible than we would consider them. Merely he is needing to make maximum use of this flexibility, and the logical conclusion of this would be that he was constrained by the other sources he is using—by the business relationship he has of what actually happened.

Davidson now turns to consider the magi and the star. He notes a certain coherence upwards to the indicate where the magi go far in Jerusalem.

Davidson now turns to consider the magi and the star. He notes a certain coherence upwards to the indicate where the magi go far in Jerusalem.

Then far, the story makes logical sense despite its theological problems (e.g. the fact that information technology encourages people to believe in the "deceptive science of astrology", every bit Strauss noted). The star is but that: a star.

Then everything changes. The star is transformed into an atmospheric low-cal that guides the magi right from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, where it hovers overa single house—the one where the child is. We are no longer dealing with a distant angelic body, simply something else entirely, similar a pixie or will-o'-the-wisp.

Hither again critical assumptions need some critical reflection. Matthew's inclusion of magi is theologically very problematic indeed. Simon Magus and Elymas (Acts 8.9, thirteen.8) inappreciably get a good press, not surprising in light of OT prohibitions on sorcery, magic and astrology. Western romanticism has embraced the Epiphany as a suggestive mystery, only earlier readings (similar that of Irenaeus) saw the point as the humiliation of paganism; the giving of the gifts was an act of submission and capitulation to a greater ability. For Matthew the Jew, they are an unlikely and risky feature to include, peculiarly when Jesus is clear he has come up to the 'lost sheep of the firm of Israel' (Matt ten.6, 15.24).

In that location have been many attempts to explain the advent of the star scientifically. The best contenders are a comet (for which there is no independence evidence), a supernova (observed by the Chinese in 4 BC) or the conjunction of Jupiter with Saturn in the constellation Pisces. I think the latter is the all-time candidate; Jupiter signified 'leader', Saturn denoted 'the Westland', and Pisces stood for 'the end of the historic period'. So this conjunction would communicate to astrologers 'A leader in the Westland [Palestine] in the end days.' This highlights a key problem with Davidson's criticism; the outcome is not whether a star could in fact bespeak a particular firm in our, modernistic scientific terms. This is clearly impossible. The existent upshot is whether Matthew thought it could—or even whether Matthew thought the magi idea information technology could. As Dick France highlights in his NICNT commentary, this was really a common agreement for which we have documentary evidence. And any naturalistic explanations miss Matthew'due south central betoken: this was something miraculous provided past God. If y'all don't recall the miraculous is possible, you are bound to discount Matthew's story—but on the basis of your ain assumptions, non on any criteria of historical reliability or the nature of Matthew'due south text.

Davidson cites the 19th-century rationalist critic David Friedrich Strauss in his objection to the plausibility of Herod's activity:

With regard to Herod's instructions to study dorsum to him, Strauss notes that surely the magi would accept seen through his plan at once. There were as well less impuissant methods Herod might have used to find out where the kid was; why did he non, for example, send companions along with the magi to Bethlehem?

In fact, nosotros know from Josephus that Herod had a fondness for using secret spies. And in terms of the story, the magi are unaware of Herod'south motives; nosotros are deploying our prior cognition of the outcome to determine what nosotros think Herod ought to accept washed, which is hardly a good basis for questioning Matthew'due south credibility.

Finally, we come up to the arrival of the magiat the home of the family. Interestingly, Matthew talks of their 'house' (Matt 2.11) which supports the idea that Jesus was not built-in in a stable—though from the historic period of children Herod has executed (less than 2 years) we should think of the magi arriving some time after the birth. No shepherds and magi together here!

Finally, we come up to the arrival of the magiat the home of the family. Interestingly, Matthew talks of their 'house' (Matt 2.11) which supports the idea that Jesus was not built-in in a stable—though from the historic period of children Herod has executed (less than 2 years) we should think of the magi arriving some time after the birth. No shepherds and magi together here!

Davidson once again sees (with critical scholars) this event synthetic from OT texts:

According to Brown, Goulder (2004), and others, the Old Testament provided the inspiration for the gifts of the magi. This passage is an implicit citation of Isaiah lx.3, 6 and Psalm 72.x, 15, which describe the bringing of gifts in homage to the king, God'south royal son.

Just once again, the problem here is that Matthew'southward account just doesn't fit very well. Given that these OT texts uniformly mention kings, not magi, if Matthew was constructing his account from these, why cull the embarrassing astrologers? And why three gifts rather than two? Where has the myrrh come from? Again, it is Irenaeus who first interprets the gifts every bit indicators of kingship, priesthood and sacrificial death respectively, but Matthew does not appear to practice so. In the narrative, they are simply extravagant gifts fit for the truthful 'rex of the Jews'. Subsequent tradition has to do the piece of work that Matthew has here failed to exercise, and brand the story fit the prophecies rather better than Matthew has managed to.

Davidson closes his analysis of this section with a final observation from Strauss:

If the magi can receive divine guidance in dreams, why are they not told in a dream to avoid Jerusalem and go direct to Bethlehem in the first identify? Many innocent lives would take been saved that way.

Clearly, God could accept washed a much ameliorate job of the whole business. But information technology rather appears as though Matthew felt unable to improve on what happened by plumbing fixtures it either to the OT texts or his sense of what ought to have happened.

The modern reader might struggle with aspects of Matthew'due south story. But information technology seems to me you lot can only dismiss it by making a big number of other, unwarranted assumptions.

(Reposted from Epiphany 2015)

Yous can heed to my sermon from Epiphany 2022 here, in which I explore historical, narrative and theological arroyo to reading this text in society to understand what nosotros might learn from it.

Follow me on Twitter @psephizo

Much of my piece of work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this post, would yous considerdonating £1.20 a calendar month to support the production of this weblog?

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/did-the-epiphany-really-happen/

0 Response to "Did Epiphany really happen?"

Post a Comment